Mary

[5.1] Many of Lincoln’s photographs were taken at the request of others. And whether through solicitation by studios or by the request of friends or colleagues, many would only come to light decades after Lincoln’s Presidency. Some were taken at the behest of sculptors or portrait painters and were never intended for public view or as works of art in their own right. Some were taken importantly as family possessions, and still others were taken specifically for political purposes. During Lincoln’s Presidency, select photographers were on rare occasion welcomed into the White House where several portraits would be taken at a sitting. At other times, months would pass without a single portrait being made. With the passage of time, these disparate and dispersed images have been incrementally brought together. As of February 2022, according to the archival staff at the Beinecke Library at Yale University: “The official number of known Lincoln photographs is debatable. There are extant portraits of Lincoln as well as non-extant portraits lost to time or yet to be rediscovered. At this point, Frederick Meserve and his intellectual descendants have identified at least 97 extant visages of Lincoln while mention of others increase the quantity to 136 images or more.”1 In contrast, there are less than 30 known images of Mary. Most of the know photographs of either Lincoln or Mary are reproduced from original prints, with their original negatives now either lost or destroyed. In Lloyd Ostendorf’s article “The Photographs of Mary Todd Lincoln,” published in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 61, Issue 3 (1968, autumn), the author states: “One reason the photographs of Mrs. Lincoln have not been catalogued heretofore is that very little concerning the dates and places of her sittings has been preserved.”

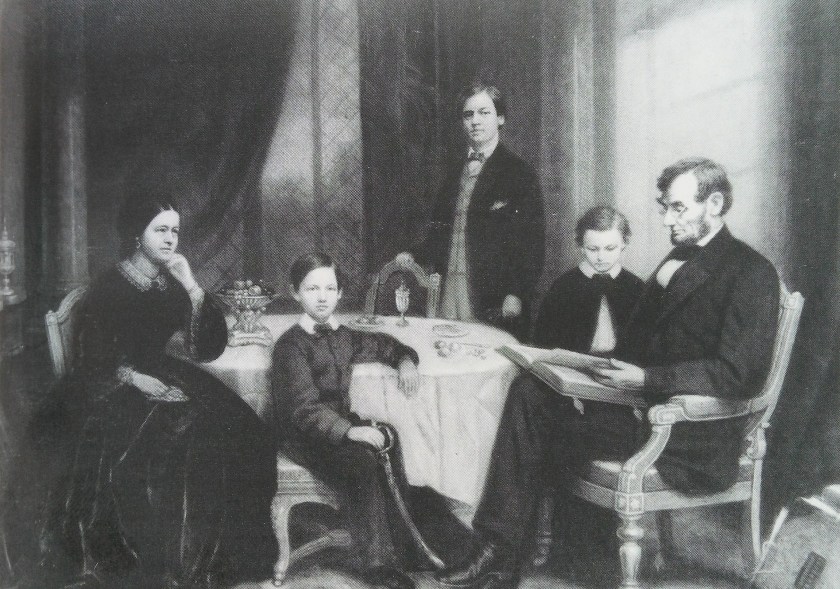

[5.2] Regarding the above photograph, Mary Lincoln wrote: “There is an excellent painted likeness of me at Brady’s in N.Y., taken in 1861 . . . in a black velvet.”2,3

[5.3] From its first public viewing, the above “painted likeness” has been an outlier with no known comparable-age photograph(s) to base further research on. Mary was quite accurate in calling the above likeness a “painting.” She was also revealing her own vanity in suggesting it was made in 1861.

In the winter of 1860-61, all the photographic galleries in America and Europe were overshadowed when Mathew B. Brady (1822-1896) opened his newest and largest studio at Broadway and Tenth Street in New York. The studio extended down Tenth Street one-hundred and fifty feet. Its interiors shimmered with elegance, its floors were covered with costly rugs, and “its luxurious couches abounded in liberal profusion.” The gallery itself was lighted with artistic gas fixtures, and its state-of-the-art heating system was a marveled-at feature. But the major attraction for visitors who crowded the studio on opening day was the vast collection of historical pictures that covered every inch of the gallery’s wall space. After a tour of the building, one reporter from Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper summed up his impression: “If Brady lived in England his gallery would be called the Royal Gallery.” (Horan, Mathew Brady: Historian with a Camera, 1965, p. 29.)

[5.4] Likely taken with a single-lens camera in which the plateholder was moved between exposures, the negative to the above image was discovered in 1954 among the Brady-Handy glass negatives purchased by the Library of Congress from Alice H. Cox and Mary H. Evans, daughters of Levin C. Handy (the grandnieces of Mathew Brady).* At the time of the purchase, the date on the protective sleeve containing the triplet negative was 1860. In 1860, it was en vogue to have a portrait print made and to have a photographer’s artist improve or accentuate the portrait with hand painting. The above example—in this case, an image with its background painted over—was clearly generated from a much earlier photograph.

*Levin Handy began his photographic career as an apprentice in the studio of his uncle, Mathew Brady. Upon Brady’s passing in 1896, Handy inherited his uncle’s stock of Civil War negatives, which were subsequently mined as a steady source of income, producing new prints from the negatives and licensing images to numerous publications. When Handy died in 1932, he left his photographic business and negatives, including those he inherited from Brady, to his daughters, Mary Handy Evans and Alice Handy Cox, who in 1954 sold the negatives to the Library of Congress, where they currently form the Brady-Handy Collection.

In 1844, at age 21, Brady had opened his first photographic studio in New York. By 1845, Brady the Commercial Photographer had become Brady the Historian, who used a camera as Bancroft had his pen. It was in that year that he began his project to preserve for posterity the pictures of all distinguished Americans in a massive volume he would later title The Gallery of Illustrious Americans. (Horan, Mathew Brady: Historian with a Camera, 1965, p. 11.)

[5.5] Apart from his own family and business concerns, Robert Lincoln spent a good deal of his adult life working to ensure that his father’s legacy was properly preserved. Many hucksters and incompetents attempted to hijack that story for the purposes of self-promotion and financial gain.

[5.6] Robert expressed doubt that there were daguerreotype studios operating in Springfield in 1846-47. Historians looking back through newspapers of the period found more than one . . . and, importantly (again seemingly), several ads for Nicholas Shepherd’s studio. These findings stirred criticism among historians that Gibson Harris’s recollections were more reliable than Robert’s. But in 1903, Harris was clearly benefited by “hitching his wagon to Lincoln’s past,” as it were, and the more unique knowledge of Lincoln’s private life that Harris could claim as his own, the better he was served. Consequently, Harris’s modest work for Lincoln (57 years prior); his knowledge of Shepherd’s studio (57 years prior); and even his alleged rooming with Shepherd (57 years prior, of which there is no evidence [Shepherd vanished into obscurity long before the claim could be verified]), hardly substantiate Harris’s suggestion that Lincoln’s presumed earliest photograph was taken at Shepherd’s studio in 1846-47. . . . Incidentally, Harris also claimed that he escorted Mary to a ball on two separate occasions on Lincoln’s behalf, which was unlikely, considering, alone, Eddie’s and Robert’s ages at the time (1 and 3 1/2 years, respectively, in March 1847); but in 1903, 56 years after the alleged fact—21 years after Mary’s passing and 12 years after William Herndon’s passing—the curious story evidently served to cleverly bolster Harris’s “trustworthiness” and perhaps, mistakenly, his credibility.

[5.7] Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives on August 3, 1846, becoming one of its then 230 members. At least one historian has contended that newly elected representatives at the time were expected to have their portraits taken for the utilitarian purposes of the larger Congress—a requirement that beginning in the early 1850s was clearly the case—but in 1847-49, in the absence of a practical photograph duplication process (collodion), was likely still years away.

[5.8] Lincoln’s first session in Congress convened on December 6, 1847. Two months earlier, the Lincolns stored their furnishings and rented out their Springfield home.4 Lincoln, Mary, and the children traveled to Washington by way of Lexington, Kentucky, where they had an extended visit with Mary’s family, the Todds. Their circuitous journey took them through St. Louis—the only city apart from Washington where, according to Robert, Lincoln’s presumed earliest photograph was likely made. Nevertheless, the Lincolns’ layover in Lexington had also afforded a measure of leisure that may have included having portraits taken. This would have been in November 1847. On the 13th of November, Henry Clay delivered his Market Speech in Lexington, with Lincoln attending.

[5.9] When Lincoln assumed his seat in the House of Representatives in December 1847, Mary accompanied him to Washington. But by April 1848, she and the children had returned to her father’s home in Lexington. The separation pleased neither party; and in May and June, arrangements were made for Mary to return to the capital. By the third week of July, Mary and the children were again united with Lincoln.

[5.10] In the same period (1847-48), while maintaining his established studio in New York, Mathew Brady expanded his business and thereby his access to prominent Americans by opening a second studio in Washington.5 To Brady’s good fortune, one of his early Washington customers was a living legend: former First Lady Dolly Payne Todd Madison (1768-1849), who introduced him to many potential customers, Mary conceivably being one (see Lincoln Lore Issue No. 838). Since images were soon routinely exchanged between the two studios, it is conceivable that Mary’s “painted likeness” (not yet painted) originated at Brady’s newly opened Washington studio in 1848, and was then years later processed (painted) and put on display as were so many others at the grand opening of Brady’s newly expanded New York studio in 1860-61. Alternatively, the original daguerreotype may have originated in Lexington or St. Louis as noted, or it may have originated at some other Washington studio entirely unaffiliated with the Brady studio . . . which may account for its painted-over background not as an expression of popular fashion, but rather as a means of hiding the identifying props of a competing studio. Whichever the case, the described image of Mary—whether its original daguerreotype, its glass negative, or its paper print copy—ended up at Brady’s New York studio in 1860-61.

[5.11] As an aside, when presidential candidate Lincoln visited New York for his famous 1860 address at Cooper Union, he was invited to the Brady studio to have his portrait taken. The resulting photograph was widely reproduced in the press and became a popular carte-de-visite. It is also of record in 1861, in New York, just prior to Lincoln’s March inauguration, that Mary met with Robert—who was attending Harvard College at the time—and the two did shop and tour the city.

[5.12] The importance of Mary’s “painted likeness” has survived principally through its rare examples in albumen prints, not its remembered display at Brady’s nor its recovered image on glass in 1954, which only served to confuse its relevance. Its original unpainted daguerreotype has in fact never materialized. And even beyond 1954, historians were not pressing for the case of Mary’s assumed earliest photograph to be reopened. By 1883, Mary was gone and could no longer have a say in the matter. In early 1896, Brady had died as well. It was not until Ostendorf’s article “The Photographs of Mary Todd Lincoln,” published in 1968, that most historians began to take greater notice of Mary’s photographic history. But even Ostendorf’s understanding of Mary’s “painted likeness” was limited by the absence of a compatible-age photograph to compare it to. From 1954 until now, Mary’s “painted likeness” has survived principally as a painting—or at best, a heavily retouched photograph—but not as a faithful representation; while, in reality, it is an exemplary example of each. . . . At the center of the one, an apparently unretouched photograph of a young and world-wise, soon-to-be world-weary, Mary Lincoln (Mary’s likely earliest photograph).

[5.13] Mary’s “painted likeness” and Eddie’s “only known” photograph (the latter discussed shortly) were each conceivably taken in 1848 at the newly opened Brady studio in Washington. A daguerreotype of Robert was also likely taken at this time but has never materialized.* Lincoln’s presumed earliest photograph was taken either in Springfield in 1846-47 (possibly at Shepherd’s studio, as Harris suggested) or at an undetermined studio in St. Louis or Washington in 1847-49 as Robert suggested—possibly at Brady’s studio, possibly at a studio in Lexington (see Dolley Madison’s July 4, 1848 photographs, which were verifiably taken at Brady’s newly opened Washington studio. [Would Gibson Harris have “recognized the work”?]).

*As suggested, Robert may have been sensitive about his own strabismus as well as his father’s. Predictably, Robert’s unmaterialized 1848 daguerreotype would have shown one or both of his eyes misaligned—the result of his inherited, not yet treated, strabismus. This unmaterialized daguerreotype may have also been inscribed with a specific date and/or a city name, of which Robert may have become intimately familiar; which would explain his later sense that his father’s presumed earliest photograph was taken in Washington or St. Louis in 1847-49, not in Springfield in 1846-47. In summary, it is reasonable to consider that Robert may have been instrumental in the “disappearance” of his own self-believed unappealing photograph as well as in the enduring unpublished existence of the subject daguerreotype itself in which his father’s as well as his own strabismus are shown.

Robert

[6.1] There are no fewer than two dozen known adolescent- and adult-age, non-daguerreotype originated photographs of Robert Todd Lincoln. (According to Friends of Hildene, there are as many as four dozen.) There are no known surviving early childhood photographs.

[6.2] Robert’s earliest known photograph was evidently taken in 1858 when he was 15. Consequently, an overlay comparison would serve little purpose. The comparisons, however, are explicit:

–Light-colored eyes

–Likely strabismus

–Diminutive chin

–Broad forehead

–Large earlobes

[6.3] It should be noted that childhood photographs of William and Thomas (Robert’s later siblings) show each suited in the exact style of clothing as is Robert in the subject daguerreotype.

Eddie

[7.1.1] As shown here on the right, there is only one known photograph of Edward “Eddie” Baker Lincoln.

[7.1.2] In the known photograph, Eddie is presumed to be three years of age (this is the age anonymously inscribed on the back of the original daguerreotype currently in the Keya Morgan collection).

Information contained in handwritten labels or tags by descendants, or later owners, while not to be ignored, must be taken at face value. Even when a daguerreotype has been preserved with a respectful sense of its historical or sentimental worth—names, dates, places, and other circumstances of its origins are easily confused and garbled in transmission from one generation to another. (Pfister, Facing the Light: Historic American Daguerreotypes, 1978, p.17.)

[7.1.3] It is the finding of this research that the known daguerreotype depicts Eddie at 2 to 2 1/2 years of age and that the subject daguerreotype depicts him at 3 years 1 to 9 months.

[7.1.4] Historians have long presumed that Eddie was likely a recurrently ill child from birth. His malady is evident in his misshapen lips in both photographs.

[7.1.5] The mortality rate for children in the mid-1800s was high. It is recorded that Eddie’s health took a debilitating turn for the worse on December 12, 1849, and that he languished for 52 days before succumbing to his illness on February 1, 1850, at the age of 3 years 10 months and 18 days (see Summary page, ¶ 12.1). Census records for 1850 list Eddie’s illness as “chronic consumption.” “Consumption” at the time was a term roughly applied to most wasting diseases. In 1850, the term “tuberculosis” was not yet used in common practice.

[7.1.6] According to Dr. Stephan Coleman, Metropolitan State University (retired), 20186 : “. . . Medical reports from the late 19th and early 20th century show a consistent association between diphtheria and tuberculosis that increased the likelihood and severity of either disease in a co-infection. These reports reveal that such a relationship was known in medical studies made in the last decades of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th century but awareness of their findings seemed to have waned as vaccination reduced the incidence of diphtheria[. . . .] In an 1894 study of the relationship between tuberculosis and diphtheria, the author asserted that neither directly caused the other, but that each created “favorable ground” for the other. A French analysis of children dying of diphtheria found 41% with latent tuberculosis; and that diphtheria was aggravated by tuberculosis, while diphtheria also awakened latent tuberculosis. Similarly, an 1896 study of 150 children with diphtheria, in St. Petersburg, reported that 39 (26%) had tuberculosis, affecting various organs. The author concluded that the presence of tuberculosis predisposed to diphtheria, diminished resistance, and worsened prognosis.”

[7.1.7] In summary, there is no conclusive evidence of exactly what Eddie died of. There is speculation that Eddie may have succumbed to medullary thyroid cancer associated with the genetic cancer syndrome multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2b (MEN2B).7 But while there is compelling evidence to make this case, most historians have maintained that Eddie likely died of complications from pulmonary tuberculosis.

Breeching

As a practical matter, before the advent of conventional diapers, male children of the western world were traditionally made to wear gender-nonspecific clothing until an age that varied between two and six years. Breeching—the transitioning into male-specific clothing (trousers and britches)—consequently became a rite of passage in the lives of male children, looked forward to with exuberance and often celebrated with a small party. The breeching ceremony had little to do with social status and was practiced across all class lines. The earliest records on breeching are found in the letters and diaries from the mid-seventeenth century. Few people, even within the upper classes, were literate in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and the fewest among these were women. As women acquired the skills of reading and writing, they used this knowledge to record important events in their lives and in the lives of their children, including the tradition by which their young sons would leave the domestic sphere of women and enter into the world of men. From at least the mid-seventeenth century until the early twentieth century most mothers planned this important event in the lives of their male children with great care. Some mothers delayed the transition for as long as possible since to some it meant the figurative loss of their boy child. Nearly all of the surviving records on breeching consist of mothers’ letters to their closest, usually female, family members or friends regarding their plans for the ceremony. Some women wrote to their mothers or other older female relatives for advice on what to do and when to do it. Others requested family or friends living in or traveling to large cities to procure various special items needed for the event. Many women also wrote about their own feelings of dread for the impending change in the lives of their little boys because it meant that their sons would be thereafter primarily under the control of their fathers. These boys would then cease to be seen as genderless children, essentially parting ways with their close bonds to their mothers to be prepared for manhood by their fathers and other prominent males of the family. Most boys were breeched at about four years of age. Some fathers would press for this to take place sooner, particularly if the child was their first-born son.

On the day of the actual ceremony, there were a few final arrangements that had to be made. If the room in which the ceremony was to be held was quite large, a folding screen might be set up in a corner behind which would be placed a chair and often a small table. The child’s new suit of clothing and its accessories would be laid out there ready to be changed into. In some homes, the clothing would be laid out in an adjoining room, apart from the room where the guests would gather, particularly if the gathering room was quite small. When all was in readiness, family and friends would gather in the main room along with the little boy and often in the accompaniment of an additional guest, the local barber. While the child had been made to wear the clothing of the nursery up until this time, his hair was also typically made to grow long. The usual first step in the breeching ceremony was the cutting of the long hair. Ordinarily, these shorn locks would then be gathered up and given to those in attendance as mementos of the event. Once the boy’s hair had been cut and combed, he would then retire behind the screen, or into the next room, to change into his new clothing, marking his first step toward manhood. . . . (Adapted from Kathryn Kane’s article “Boy to Man: The Breeching Ceremony,” The Regency Redingote, 2012.)8

[7.2.1] Point 1 of 3 to keep in mind: In the subject daguerreotype, the subject Eddie’s clothing also has a photographic purpose; it hides the two risers that Eddie and his mother are separately seated on. Lincoln stood 6 feet 4 inches; Mary, 5 feet 2 to 4 inches. The length of Eddie’s garment and its impracticality for his general use suggest that it was selected/provided (conceivably by the photographer) methodically for the purpose of hiding the described risers.

Lincoln

[8.1] In the subject daguerreotype, the subject Lincoln’s hair is parted on the traditional side. However, daguerreotypes, unlike conventional photographs, are left-right reversed (mirror) images. So when Lincoln sat for the subject daguerreotype, his hair was parted on the opposite side from what was typical for him in later photographs.

[8.2] There are no less than seven known non-daguerreotype originated photographs in which Lincoln’s hair is parted on the nontraditional side (Meserve Nos. 79, 80, 81-82, 85, 86, 87, 127, etc.). There are also no less than three known photographs in which Lincoln’s hair is combed straight back with no part at all (Meserve Nos. 21, 22, 122, etc.).

[8.3] Point 2 of 3 to keep in mind: In the subject daguerreotype, the overhead lighting is necessarily intense,9 creating a representation of Lincoln not seen in other photographs. Suffused with intense sunlight, the subject Lincoln’s eyebrows are faintly evident, although under handheld magnification their outline and texture can be clearly seen (this clarity to be improved with the eventual cleaning of the interior glass of the subject daguerreotype).

[8.4] Point 3 of 3 to keep in mind: Lincoln’s chin was more dimpled than clefted. What is apparent in the subject daguerreotype is that this feature did not imbue well with the intense lighting.9 What is evident is that the photographer retouched this deficit, placing his effort slightly off-center, which becomes more obvious as the image is enlarged.

Perspective Complexities

[9.1] Although all of the known photographs of Lincoln were taken within a 16- to 19-year time span, they give a widely diverse impression of his physical appearance. Initial and later retouching account for a portion of this—as do lighting, head angle, body posture, facial demeanor, weight fluctuation, beard growth, temporal wasting (indicative of aging or declining health), and as likewise do other age-related physicality changes as well as perspective complexities incurred technically and technologically when certain photographs were originally made. (The word “perspective” refers here to the spatial relationship between the subject being photographed and the viewpoint of the camera. A camera lens can render a complex image due to: 1] the angle of its viewpoint, 2] the position of its subject, and 3] a variety of optical [lens] peculiarities.)

Mid-nineteenth century camera lenses were very different from the compound lenses used today. Lincoln had a very pronounced nose, but in many of his photographs he seems to have a very small nose. He looks better in his photography than he actually did in real life. The other thing about Lincoln was that over time his face grew increasingly asymmetrical. [In 1860, one year before Lincoln assumed the presidency, he had a life mask made. Five years later (two months before April 14th), he had a second life mask made. The two masks still exist today. The right and left halves of Lincoln’s face grew in five years to look as if they belonged to two different people.] In the photography, photographers are increasingly photographing Lincoln from only his better side, which was his right side. They’re changing the part of his hair. There are all of these kinds of things going on, including lens distortion. The very long lenses subdue his nose and subdue his ears, and create an illusion of a better-looking face than Lincoln actually had. . . . (Adapted from Ray Downing’s [Studio Macbeth] article/interview “Creating New Video Footage of Abraham Lincoln,” Studiodaily, 2009.)

[9.2] There were lens manufacturing issues, glass quality issues, image compression and magnification issues—as well as issues that affected viewer perception but are not considered aberrations. For example, oblique lighting and focus falloff, sometimes called “natural vignetting,” and even, seminally, the inherent geometric effects of simply projecting a three-dimensional reality onto a two-dimensional field. In mid-nineteenth century photography, the most commonly used lens for portraiture—”The Petzval Portrait Lens”—was an unpatented design produced and sold derivatively by many different manufacturers with varying disciplines of perfection. The typical angle of view of this lens was 45 to 15 degrees, which is equivalent to the 45mm to 150mm focal range of a full-range SLR camera. Lincoln sat for 30+ different cameramen on 60+ different occasions. His photographs were taken with many different cameras with many different lenses. And although none of these factors actually alter perspective, they do affect how perspective is recorded and later perceived in a photograph.

[9.3] When we look at a picture—whether a painting, a movie, a television image, or a photograph—what we are seeing is a two-dimensional surface. But what we imagine we are seeing is a three-dimensional view stretching in from the picture plane.

[9.4] When we look at a daguerreotype, what we are seeing is a two- as well as a three-dimensional view, culminating in an image comparable to a hologram.

[9.5] When a secondary photograph is taken of a daguerreotype (as per necessity it must for the purposes of this website or for any other publishing purpose), what we are then seeing is a two-dimensional representation of the original representation.

[9.6] All of these complications are analytically resolvable by simply understanding their implications.

1849-1853

[10.1] As mentioned from the outset, the subject daguerreotype (taken in 1849) is earlier than Mary’s assumed earliest photograph taken in the early 1850s.

[10.2] Between the time the subject daguerreotype was taken in 1849 and Mary’s assumed earliest photograph was taken in the early 1850s, Mary had suffered the loss of her then-youngest child, Eddie (Feb. 1850); she had given birth to her third child, William (Dec. 1850); and she was likely either pregnant with or had given birth to her fourth child, Thomas (April 1853).

[10.3] In Mary’s assumed earliest photograph, the weight gain or water retention (edema) evident in her face is plausibly a result of her pregnancy. Contributing factors may have also included high sodium intake and vitamin deficiency—including together or alone vitamin(s) D, B2, B5, B6, and B12. It is known that Mary suffered from chronic migraines and that a residual effect of this affliction—particularly long term—is ptosis. It is also known that vitamin D deficiency is a contributing factor in both migraines and edema. It is not known to what extent Mary resorted to medicinal pain alleviation, which may have also contributed to her condition.

[10.4] As part of the time-age continuum of natural biology, other factors notwithstanding—e.g., the residual effects of environment; injury; illness; dental occlusion or deterioration; diet; substance (medicine) use (prescribed or otherwise) or abuse; etc.—the age-related changes to a person’s facial features are inherently determined by gravity and genetics. These factors continue over time to impart and evolve, inclining typically the nose, for example—in a uniquely individual way and over a uniquely individual course of time—to discernibly slump downward and the outer areas of the nostrils to widen (the skin loses its elasticity; the cartilage softens, weakens, and becomes brittle; and the sections of cartilage that attach to the top and bottom areas of the nose sometimes separate)—all genetically and gravitationally predisposed, and to a measurable extent resolving between late-early and early-late adulthood.

[10.5] In FIG. 16, if we measure the distances between Mary’s irises in the two compared images, we discover that the two measurements are slightly different. This is an example of how an incomplete understanding of perspective complexity can lead to a considerable misunderstanding in facial identification. With all things being equal, the measurements should be the same. But as we look closely at the compared images, we discover that in Mary’s assumed earliest image her head is turned slightly to one side and in her subject image she is facing straight toward the camera. This small yet significant difference in head-turn angle has a clear bearing on the distance between irises as seen in a photograph. As illustrated in the video below, the farther a face is turned left or right, the narrower the distance between irises as seen in a photograph will appear to be.

[10.6] To further clarify the above point, in the overlay comparison below—comparing the subject Mary, age 30-31, to Mary, age 50—with each image facing straight toward the camera, the distances between the compared irises are in fact the same.

[10.7] Eye size and eye separation vary slightly from person to person, as does iris diameter. With rare exception do these dimensions with respect to an adult appreciably change with time. To standardize an overlay comparison such as the one shown above, the irises are sized identically in each image. The identically sized irises are then overlaid precisely, one over the other. For a comparison to then be a match, the remaining facial features—allowing for age disparity—must then match in location, shape, and size. However, such images are rarely originally photographed in the same posture or from the same camera angle—i.e., typically, the turn and tilt of each image is slightly different in each photograph. In such cases, an overlay comparison will result in none of the remaining features lining up precisely, but rather all of the features being the same degree misaligned. So rather than attempting to line up all of the features precisely or showing all of the features the same degree misaligned, the irises alone are lined up and the remaining features are sensibly compared.

[10.8] As noted in FIG. 17, pertaining to portrait photography, the height position of a person’s ears in relation to the features of his or her face—due to the ears being situated on the side of the head, not the front of the face—is affected by three factors: 1) the height position of the camera, 2) the tilt [forward or back] position of the head, and 3) the tilt [forward or back] position of the upper body.

[10.9] As further noted in FIG. 17, the appearing vertical distance between the tip of the nose and the center of the mouth is likewise affected by the above three factors, and, additionally, by the angle and distance the nose is extended.

[10.10] A more deceptive example of perspective complexity can be seen in the photographed angle of Mary’s outer eyelid joints (i.e., the points where her upper and lower eyelids meet farthest from her nose).

[10.11] Eyelids are not set on a straight horizontal plane, but rather on a curved horizontal plane, which is the left-right horizontal curve of the face. The point where a single eye’s eyelids meet farthest from the nose is actually located on the side of the face, not the front. Consequently, as the head is tilted forward or back, the front-on perspective of where the eyelids meet farthest from the nose is vertically affected differently than the front-on perspective of where the eyelids meet closest to the nose (which is inversely located on the front of the face, not the side).

Reappropriated Skills and Hidden Realities

[ . . .]Oil on canvas portraits, typically measuring 30 by 25 inches, were intended to dominate parlor walls, displaying the sitter’s gentility and position. From their earliest invention, reaching back hundreds of years, these were affordable only to the wealthier spectrum of society. Even in the early 1830s, academic portrait painters often demanded $60 to $100 (the equivalent of $2188 to $3646 in 2024 dollars) for these works of art, and even non-academic folk artists charged between $15 and $30 (the equivalent of $547 to $1094 in 2024 dollars). Miniature portraits on ivory generally started at $8. For the average American, small portraits typically painted on bristol board, with prices ranging between 25¢ and $4, became the affordable alternative[. . . .]

For two decades before the commercial advent of photography, miniature painted portraiture was the dominant portrait style in America. Produced in both rural towns and major cities, the importance of these small possessions to the average American was profound[. . . .]

People from all walks of life eagerly sought these affordable small portraits, and numerous artists—using ink, pencils, and watercolors—specialized in their production. Most of the artists were itinerants who found commissions by traveling between cities and small towns. Some distributed advertising cards in doorways and returned the next day to show samples[. . . .] (Adapted from Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael R. Payne’s article “Images of the American People: Small Portraits From 1820 to 1850,” Incollect magazine, 2014, Jan. 8.)

From the early 1820s, these small painted portraits were a major aspect of America’s artistic accomplishment. Capturing the endearing likenesses of the family, they were the portraits of the heart for the average American. This affection would set the stage for photography. Starting in the early 1840s, small painted portraits were gradually displaced by daguerreotypes, which provided images that were novel, affordable, and more precise[. . . .] (Adapted from Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael R. Payne’s article “Images of the American People: Small Portraits From 1820 to 1850,” Incollect magazine, 2014, Jan. 8.)

[11.1] At their crossroads, newly pioneered photography and well-established miniature portrait painting held what appeared to be competing roles. In the end, this didn’t really matter. Photographers and miniature portrait artists shared ideas, techniques, and even customers. The best artists continued to ply their trade. Many others either gave up miniature portrait painting altogether or switched over to photography where they were able to reappropriate their considerable skills.

[11.2] As an exclusively black and white medium, with color added only by hand, a little remembered phenomenon of the daguerreotype era is that certain original colors were sometimes adversely affected in the daguerreotype chemical process. For example, yellows and reds would often transpose very dark. In the case of the subject daguerreotype, Lincoln’s coat was predictably black in color and consequently its darkness transposed identically so. But Mary’s dark appearing satin dress, with its original color unknown and un-presumable, may have actually been red or yellow.

[11.3] In 1849, a sixteenth plate daguerreotype portrait (1 3/8″ × 1 5/8″) typically cost $1.25 to have made (the equivalent of $50.36 in 2024 dollars); a sixth plate daguerreotype portrait (2 3/4″ × 3 1/4″; the most popular size) typically cost $1.50 to have made (the equivalent of $61.08 in 2024 dollars); and a quarter plate daguerreotype portrait (3 1/4″ × 4 1/4″; the size of the subject daguerreotype) typically cost $2 to have made (the equivalent of $81.44 in 2024 dollars). The quality of a customer’s chosen encasement and the extent of requested hand colorization could more than double the basic price.

In Lincoln’s era it was an accepted practice to retouch or alter photographs[. . . .] All photographers did it[. . . .] (Ostendorf, Lincoln’s Photographs: A Complete Album, 1998, p. 256)

Brady took the pictures—artists “improved” them. (Ostendorf, Lincoln’s photographs: A Complete Album, 1998, p. 268)

[11.4] In the early decades of commercial photography—prior to the mid-1870s, when most customers actually welcomed or encouraged having their portrait retouched—most customers were unaware of the license often taken in photographic portraiture. Photographers and their artists (often one and the same) quickly learned which areas of a photographed face could be easily “adjusted” without drawing undesired attention. Technically, the aim was not to alter reality, but rather to improve a customer’s experience and to advance the lot of the portrait studio. In some cases a portion of a customer’s wrinkles might be smoothed over or his or her nasolabial folds might be “softened.” More commonly a customer’s eyelids might be retraced to compensate for being too faintly “captured.” This delicate, minimal work was done traditionally with the intention of improvement.

[11.5] With famous subjects—Lincoln included—alterations were commonly made even years later, completely removed from the oversight and wishes of either the subject or the original photographer.

[11.6] According to George Schneider, once editor of the Illinois Staat-Zeitung (the most anti-slavery newspaper in the West), by 1853, Lincoln “was already a man necessary to know.”

[11.7] From 1854 through 1865 and far into the 20th century, an effort was expended to portray Lincoln’s photographic image in its best possible light. Whether imposed intuitively by original photographers at the time of creation or more methodically by others on subsequently created photographic copies, most of the surviving images of Lincoln have been extensively altered. Today, with the majority of their originals either lost or destroyed, the farther a Lincoln image is generationally removed from its original; that is, developed into prints or from prints into copies of prints—whether through stereograms, cartes-de-visite, cabinet cards, news printings, book publishings, etc.—the greater the extent an image has likely been altered. Lincoln’s eyelids were routinely retraced. His upper lip was sometimes widened to compensate for his oversized lower lip and his ears were sometimes altered to make them appear less obtrusive. Lincoln’s forehead was commonly retouched with thinner, straighter furrow lines and his nasolabial folds were sometimes darkened, redrawn, or repositioned. The rough areas under Lincoln’s eyes were routinely smoothed over—a common method being to heavily retouch the areas closest to the camera and less heavily the areas farthest from the camera, but as often as not with both areas being significantly affected.

Photos

Fig. 20. Lincoln (left), age 49, photograph taken by Abraham M. Byers on May 7, 1858. Lincoln (right), age 49, photograph taken by T.P. Pearson on August 26, 1858. The above two images, taken three months apart, reveal the degree to which Lincoln’s photographs were commonly retouched. Looking back through Lincoln’s photographs, dating from 1854, the areas under his eyes were routinely retouched as was his forehead.

[11.8] The purpose of clarifying the extent to which Lincoln’s images were retouched is to make aware the fact that in the realm of Lincoln photographic comparisons, altered images are typically the representations being compared to. Not that this prohibits authentication; if anything, this clarification makes a conclusion easier to accomplish. But a clear understanding of these complexities is imperative to this end.

[11.9] To better understand this point, apart from other inconsistencies, compare closely Lincoln’s ears in the following two representations.

[11.10] The image on the left is from the dust jacket of a celebrated book published in 2014, and the image on the right is from the cover of a book published in 2018.

[11.11] Typically, the more accurate image will be the image closest generationally to the original photograph (but, again, even the original photograph can be altered or retouched).

[11.12] Below, downloaded from the Library of Congress website, is an early print of the same image.

[11.13] The downloaded print makes clear with respect to Lincoln’s ears that the image on the 2018 book cover is more accurate than the image on the 2014 dust jacket. It also illustrates the point that comparison images must be carefully researched before being selected.

[11.14] Below, downloaded from a second source, is an additional print variant of the same photograph.

[11.15] What is gleaned from the above variations—and particularly so in light of no other photographs being known to exist of Lincoln with his face essentially parallel to the camera—is that there was an issue (possibly Lincoln’s own) regarding Lincoln’s photograph being taken from this angle.

[11.16] As one looks closely at the above image, Lincoln’s wider-appearing proper right temple and his slightly leftward-angled nose indicate that his proper right ear should appear more prominently then his left ear but isn’t the case due to his right ear being retouched.

[11.17] As we look closely at the subject Lincoln’s ears, the mystery unravels: compositionally, the size and shape of Lincoln’s ears, as viewed from the described angle, draw disproportionate (unfavorable) attention. In the image above, Lincoln’s proper right ear has been retouched to make both ears appear less distracting.

[11.18] Historians have long contended that Lincoln aged disproportionately during his four years as President . . . which isn’t hard to conclude, based on a cursory appraisal of his surviving images. The fact is, Lincoln looked much older than his years long before he became President, a reality that his retouched images successfully conceal. On February 5, 1865, Lincoln had a series of five photographs taken by Alexander Gardner for the purposes of the American portraitist Mathew Wilson. Wilson had been commissioned to paint the President’s portrait, but because Lincoln could spare so little time to pose, the artist needed recent photographs to work from. The five images were never intended for public view. Consequently, they were sparingly retouched.

[11.19] The above considerations must all be accounted for in any comprehensive Lincoln photograph analysis or comparison.

Notes

1. (¶ 5.1) In James Mellon’s book The Face of Lincoln (New York: Bonanza Books, 1979), the author states:

At least 136 photographic poses or views of Lincoln are believed to have existed [past tense]. Among the 120 that survive, either in original form or as copies, there are daguerreotypes (images on silver-plated copper); tintypes, also known as ferrotypes (images on japanned iron); ambrotype (glass collodion negatives converted into positives by the addition of a dark background); various sizes of gold-toned images, including stereographic cards and cartes-de-visite, all printed on albumen paper from glass collodion negatives; and a few salt prints and glass positives, also printed from collodion negatives[. . . .]

Of the 102 surviving poses known to, or believed to, have originated as glass collodion negatives made for print, there are only 24 for which an original, or suspected original, negative can still be found. The remaining 78 poses survive only as original prints or copies of the lost originals. All but a few of the remaining original negatives are severely cracked, scratched, or broken, or suffer from deteriorating emulsion. Of the fourteen existing poses known to, or believed to, have originated as ambrotypes, only four survive in the original. Of the known original daguerreotypes, one survives [Meserve No. 1]. And at least sixteen poses of Lincoln are believed to have existed, of which not a single likeness remains.

In Lloyd Ostendorf’s book Lincoln’s Photographs: A Complete Album (Rockywood Press, 1998), the author states:

Lincoln sat for 36 different cameramen on sixty-six occasions. Alexander Gardner took thirty-six of his photographs, more than any other photographer. Anthony Berger is second with thirteen; Brady is third with eleven. Preston Butler also took eleven photographs of Lincoln, but only three survive. Lincoln had his picture taken in seven states. Sixty-nine photographs, over half of those known, were posed in Washington, D.C. Thirty-two were taken in Illinois. There exists 130 separate photographs of Lincoln, 40 beardless and 90 with beard. Among that number are 36 stereoscopic or three dimensional views[. . . .] There are two daguerreotypes known to have been taken of Lincoln, one tintype (or ferrotype), 12 ambrotypes, and 116 wet-plate collodion photographs. The daguerreotypes (on silvered copper) and the tintype (on tin black iron) gave only one portrait for each exposure. The glass ambrotype mounted against a dark background sometimes served as a negative to make positive paper prints. The wet-plate collodion method produced a negative glass plate from which any number of copies on paper could be turned out.

2. (¶ 5.2) Ruth Painter Randall, Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1953), opposite p. 328.

3. (¶ 5.2) Mark E. Neely Jr., and Harold Holzer, The Lincoln Family Album (Southern University Press, 1990), p. 85:

After April 14, 1865 [. . . ] Americans clamored for portrayals of the Lincoln family together, eager to visualize the war-weary leader as they imagined he looked in the comforting bliss of domestic life—even if, in reality, such refuge rarely existed for him.

To overcome the absence of a group photograph that could be used as a model, many engravers and lithographers created composites based on available portraits of individual family members. Most of the results were awkward and inaccurate, but one composite family scene was carefully researched, artistically assembled, and modeled in part on pictures from the Lincoln family album. Commissioned soon after April 1865, it was the brainchild of artist Francis B. Carpenter[. . . .]

Mary proved eager to help Carpenter, but when the artist asked her to pose for a new photograph, she declined[. . . .] Instead she urged Carpenter [in a November 15, 1865 letter] to consult what she termed “an excellent painted likeness of herself . . . taken in a black velvet.” [Mary’s “painted likeness” was thereby the model used for Mary’s depiction in Carpenter’s composite family scene.]

4. (¶ 5.8) Upon returning to Springfield in 1848-49, the Lincolns lodged at the Globe Tavern until their rented-out home could be relinquished and renovated. The Globe Tavern was a boarding house where Lincoln and Mary first lived as newlyweds in 1842. Robert was born at the Globe in 1843, and soon thereafter the Lincolns moved into the only house that they would ever own at 413 South 8th Street.

5. (¶ 5.10) Mathew Brady’s initial foray into establishing a branch studio in the City of Washington in 1847-48 was a modest and measured experimental endeavor, with a more substantial studio being opened in 1849.

6. (¶ 7.1.6) Stephen Coleman, PhD, “The Association Between Tuberculosis and Diphtheria.” Epidemiology and Infection, 146(8) (2018 June).

7. (¶ 7.1.7) John G. Sotos, MD, The Physical Lincoln (Mount Vernon Book Systems, 2008).

8. (¶¶ Breeching) In 2017, Kathryn Kane further commented that “[t]he breeching ceremony is a particularly esoteric topic, for which there is little published information.” She acknowledged that her own understanding of the subject was “gathered over a long period of years as a graduate student, museum curator and in continued research throughout [her] life. . . .”

In the subject daguerreotype, the subject Eddie—in addition to his hair being overlong—is the only sitter with his hair unkempt. Eddie may have been unreasonably sensitive to having his hair brushed or combed—a common symptom of a condition known today as Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD). In light of Eddie’s poor health, it may have been a concession on Mary’s part to simply let him have his hair his own way. (SPD is a hereditary disorder of which Mary’s occasionally overwrought temperament—for example, her apparently unreasonable fear of thunderstorms—may have also been a symptom).

9. (¶¶ Fig. 11; 8.3; 8.4; see also Instruction page, OVERLAY COMPARISON “B”) Prior to the 1860s, a painted family portrait composed of a man with his wife and children was rare . . . which is not to say that down through history such paintings were never made. However, prior to the 1860s, men were traditionally more reserved with their affections toward their children, whether in public or as implied in a portrait. Husbands and wives commonly posed together as well as separately; but, typically, mothers posed with their children, and fathers posed alone. This formality carried over into early photography, but not entirely for the same reasons. Predating electric light, mid-nineteenth century studio photography was illuminated by sunlight typically admitted through a window or a ceiling skylight or both. Daguerreotypes made in the 1840s could require long exposure times, depending on the ambient light available and the requirements of the daguerreotype being made. With respect to the subject daguerreotype, this challenge was compounded by its multiple sitters and further by two of its sitters being young children. To successfully make the photograph, all four subjects had to remain perfectly still for as long as the daguerreotypist judged necessary, which could be as little as 8 to 10 seconds under direct sunlight or as long as 20 seconds or more under less intense light. To improve the odds of success—i.e., to ensure that each sitter would remain perfectly still for the duration of film exposure—group portraits were methodically illuminated with the brightest sunlight, which allowed for the shortest exposure time. . . . But this was hardly an ideal arrangement. Apart from the inherent imperfections of the over-lit image, the trial-and-error process of making a satisfactory full-family portrait in which no one blinked or moved was not only predictably onerous (fraught with failed attempts), it was predictably quite expensive. For these reasons, the 1849 daguerreotype of Lincoln, Mary, Robert, and Eddie is not only an extraordinary Lincoln artifact, it is a rare example of mid-nineteenth century photography. (Note: To see straight-on view of the subject daguerreotype, continue to the Contact page and scroll down three page lengths to the Pi symbol located at the left margin, and then click on the symbol.)

References

Coleman, S., PhD. (2018 June). The association between tuberculosis and diphtheria. Epidemiology and Infection, 146(8).

Downing, R., (Studio Macbeth). (2009). Creating new video footage of Abraham Lincoln. Studiodaily.

Emerson, J. (2019). Mary Lincoln for the Ages. Southern Illinois University Press.

Harris, G. W. (1903-1905). My recollections of Abraham Lincoln. Various periodicals (Woman’s Home Companion, etc.).

Horan, J. D. (1965). Mathew Brady: Historian with a Camera. New York: Bonanza Books.

Kane, K. (2012). Boy to man: The breeching ceremony. The Regency Redingote.

Mellon, J. (1979). The Face of Lincoln. New York: Bonanza Books.

Neely, M. E. Jr., and Holzer, H. (1990). The Lincoln Family Album. Southern Illinois University Press.

Ostendorf, L. (1998). Lincoln’s Photographs: A Complete Album. Rockywood Press.

Ostendorf, L. (1968, autumn). The photographs of Mary Todd Lincoln. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 61(3).

Payne, S. R., and Payne, M. R. (2014, January 8). Images of the American people: Small portraits from 1820 to 1850. Incollect. https://www.incollect.com > articles

Pfister, H. F. (1978). Facing the Light: Historic American Portrait Daguerreotypes. National Portrait Gallery (Smithsonian Institution Archives).

Randall, R. P. (1953). Mary Lincoln, Biography of a Marriage. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Sotos, J. G., MD. (2008). The Physical Lincoln. Mount Vernon Book Systems.

Copyright © 2023-2025 P.A. Epperson. All rights reserved.